PUBLICATIONS

On Art and Science in Research Practice.

Part 1

Part 1

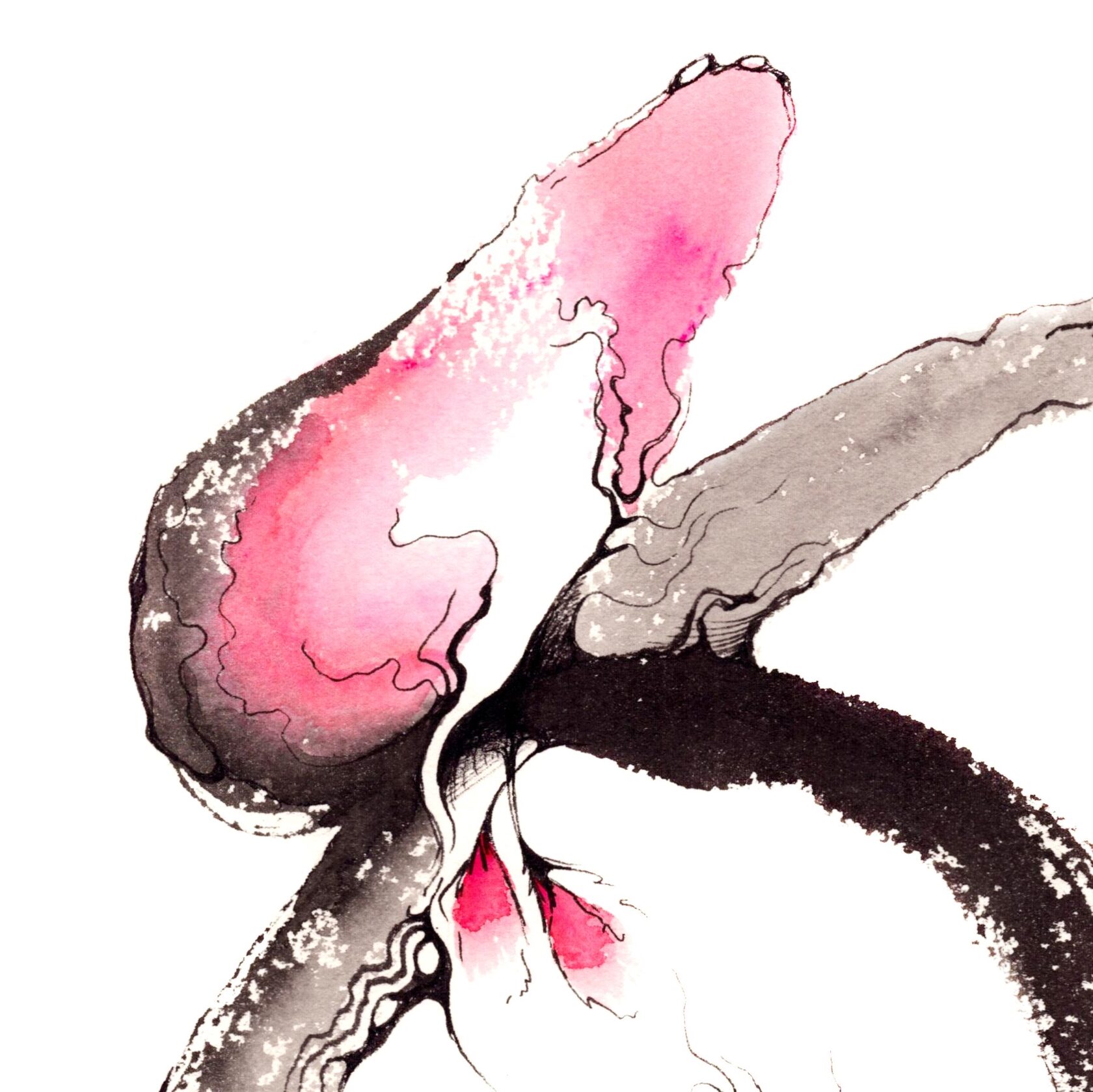

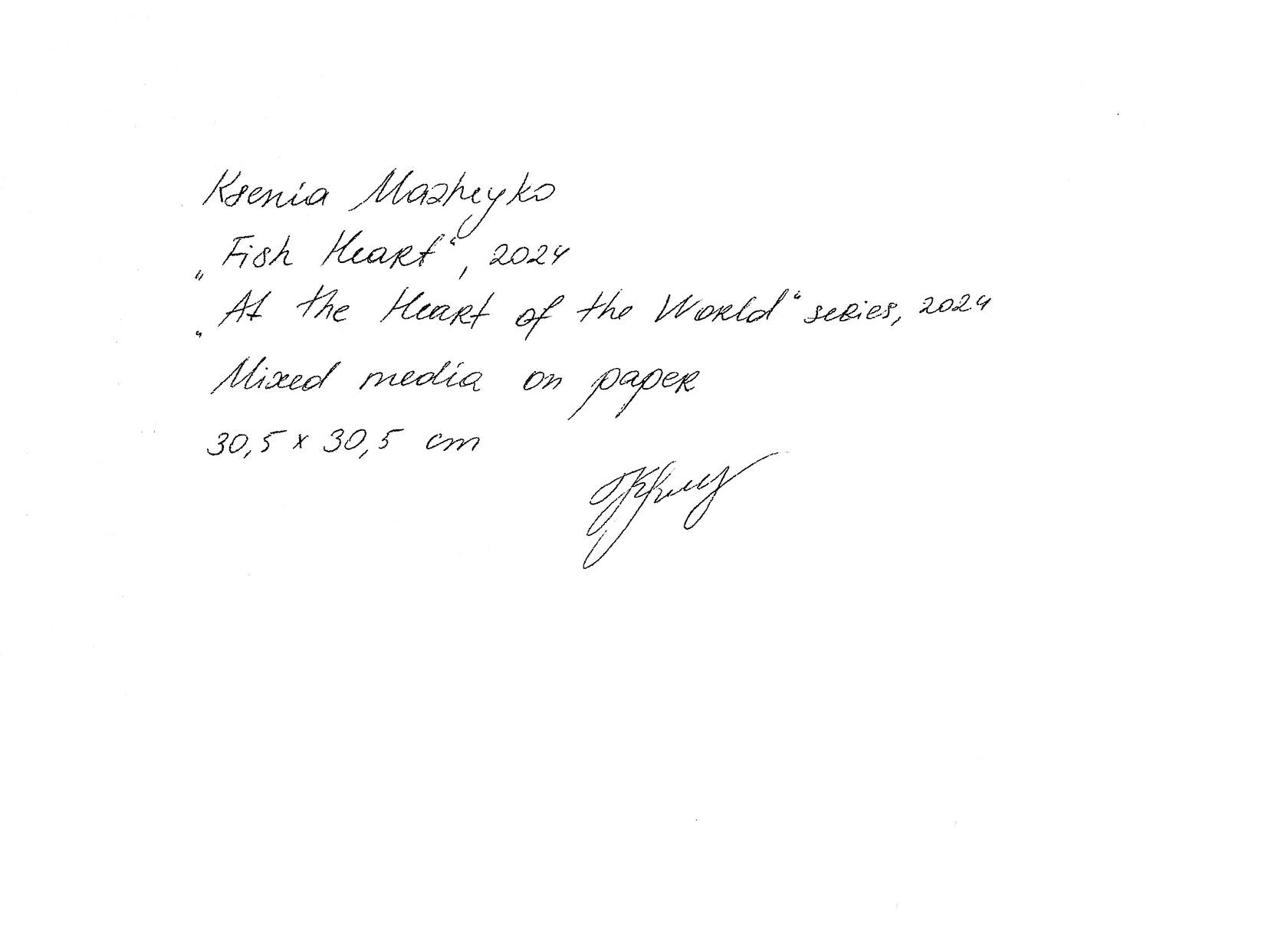

Ksenia Mazheyko, artist based in Spain

@kseniamazheyko.art

@kseniamazheyko.art

At the very first class, the new teacher looked at my barely started drawing and asked, “What’s your method?”

Suddenly, I felt a draft blow through the empty space in my mind — that question simply didn’t compute. A method? Aren’t we here to make art? What kind of “method” could I possibly have?

Method — that’s science talk. Experiments, formulas, calculations... all the things artists usually try to avoid. Let the philosophers define methods, let the scientists follow them — if they’re so fond of rules, definitions, and constraints. But we, the artists — we’re driven by the beauty of the moment. We thrive on inspiration, freedom, creative impulse, the sheer excess of inner life.

Suddenly, I felt a draft blow through the empty space in my mind — that question simply didn’t compute. A method? Aren’t we here to make art? What kind of “method” could I possibly have?

Method — that’s science talk. Experiments, formulas, calculations... all the things artists usually try to avoid. Let the philosophers define methods, let the scientists follow them — if they’re so fond of rules, definitions, and constraints. But we, the artists — we’re driven by the beauty of the moment. We thrive on inspiration, freedom, creative impulse, the sheer excess of inner life.

A method? Seriously?

That brief moment — despite the mental draft it stirred — stuck with me.

First, because the teacher was a true master, someone who wouldn’t ask a pointless question.

And second, because, somewhere in the back of my mind, it echoed a conversation I’d had with a neuroscientist not long before. She was explaining how to analyze tissue samples (I’ll spare you the details), and at one point she said it was important to pay attention to the “beauty of the structures.”

That stunned me. In my world, “beauty” is far too subjective to be useful in something as serious as scientific research.

It felt like two impressions had collided in my head — staring at each other, unable to figure out what they were supposed to do with one another. That encounter didn’t belong in my neural landscape and disrupted the tidy order I thought I had there.

Sure, like many others, I’ve seen The Da Vinci Code, and I know all about the Fibonacci numbers in his works. At school, we heard how mathematicians admire the “beauty” of proofs, and how Bach’s fugues are like entire mathematical universes. But none of that ever impressed me as deeply as these two small, real-life encounters.

These lived paradoxes — raw, personal — illustrated the hidden connection between art and science far more vividly than the name of Faust’s author printed on an old volume of optical studies ever could.

And since my family is known for its relentless intellectual curiosity, it was only natural that I’d want to explore the question further.

I wasn’t satisfied with the countless examples of scientists who paint in their spare time or artists who embrace cutting-edge tech in their work — the usual way most sources describe the art-science link.

The now widespread term Science Art refers only to those artistic practices that align themselves with the technological sciences. And that’s just one narrow facet of a much deeper, more mysterious relationship.

That brief moment — despite the mental draft it stirred — stuck with me.

First, because the teacher was a true master, someone who wouldn’t ask a pointless question.

And second, because, somewhere in the back of my mind, it echoed a conversation I’d had with a neuroscientist not long before. She was explaining how to analyze tissue samples (I’ll spare you the details), and at one point she said it was important to pay attention to the “beauty of the structures.”

That stunned me. In my world, “beauty” is far too subjective to be useful in something as serious as scientific research.

It felt like two impressions had collided in my head — staring at each other, unable to figure out what they were supposed to do with one another. That encounter didn’t belong in my neural landscape and disrupted the tidy order I thought I had there.

Sure, like many others, I’ve seen The Da Vinci Code, and I know all about the Fibonacci numbers in his works. At school, we heard how mathematicians admire the “beauty” of proofs, and how Bach’s fugues are like entire mathematical universes. But none of that ever impressed me as deeply as these two small, real-life encounters.

These lived paradoxes — raw, personal — illustrated the hidden connection between art and science far more vividly than the name of Faust’s author printed on an old volume of optical studies ever could.

And since my family is known for its relentless intellectual curiosity, it was only natural that I’d want to explore the question further.

I wasn’t satisfied with the countless examples of scientists who paint in their spare time or artists who embrace cutting-edge tech in their work — the usual way most sources describe the art-science link.

The now widespread term Science Art refers only to those artistic practices that align themselves with the technological sciences. And that’s just one narrow facet of a much deeper, more mysterious relationship.

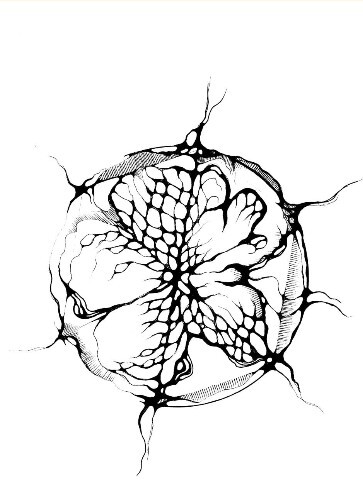

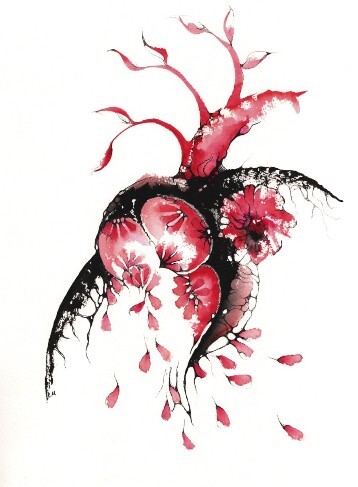

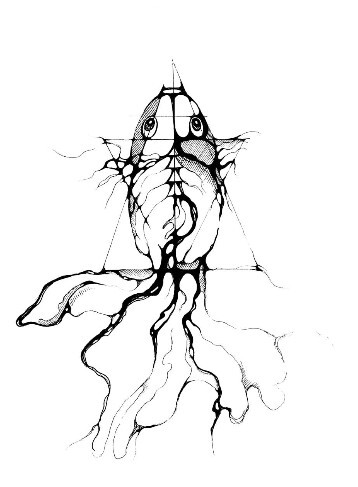

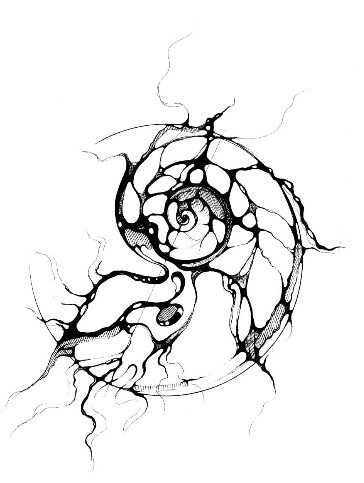

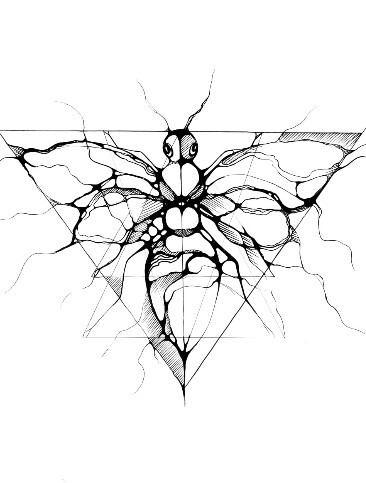

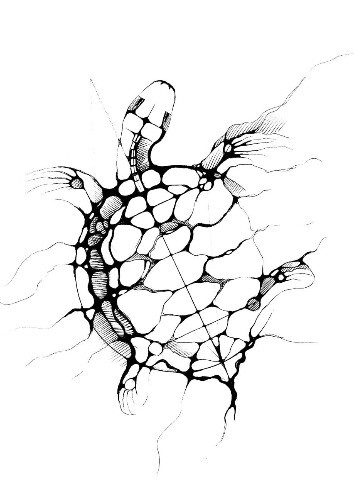

More artworks

First and foremost, digital sciences, genetics, and all branches of biomedicine. Simply put, modern Science Art is cutting-edge scientific knowledge realized in an artistic form. In other words, it is a type of creativity where science serves as the medium and materials, while art provides the form. Indeed, this results in a powerful, multilayered statement that appeals both to the general public and to specialists.

Nevertheless, as I delved deeper into my archive of ideas, knowledge, and impressions, I found myself increasingly inclined toward the idea that the connection between art and science lies not in their outward expression or statement, but in the very nature of these two forms of creativity. “Science and art are the two eyes through which humanity views the world,” Yuri Lotman once said. And he was not alone in this belief. This connection MUST exist at the level of brain function, or motivation, or both together. Both art and science are uniquely human activities. Therefore, their nature and the relationship between them are best explained through the nature of the human being—specifically, through brain activity.

Today, an enormous number of studies on brain function at the intersection of neurophysiology and psychology are being conducted worldwide! It would be wonderful to participate in one personally, but for now, I must limit myself to theoretical study, constantly reflecting on everything I learn. Beauty, method and intuition, analysis and synthesis, interpretation, imagination, irregularity, illogic, surprise, counterintuitiveness — these concepts buzz endlessly in my mind.

Regarding the nature of both artistic and scientific activity, my still non-professional understanding insists that both art and science, at their extremes, unfold at the border between the known and the unknown. Artists and scientists strive to break through the barrier, to overcome the transcendental gap between the “familiar, safe” and the “unknown, threatening.” They seek to make the borderline — dangerous in its uncertainty — more comprehensible and safe. Presumably, there is a certain value in overcoming and expanding boundaries, which is why humans are defined as “beings who always strive for more.”

Nevertheless, as I delved deeper into my archive of ideas, knowledge, and impressions, I found myself increasingly inclined toward the idea that the connection between art and science lies not in their outward expression or statement, but in the very nature of these two forms of creativity. “Science and art are the two eyes through which humanity views the world,” Yuri Lotman once said. And he was not alone in this belief. This connection MUST exist at the level of brain function, or motivation, or both together. Both art and science are uniquely human activities. Therefore, their nature and the relationship between them are best explained through the nature of the human being—specifically, through brain activity.

Today, an enormous number of studies on brain function at the intersection of neurophysiology and psychology are being conducted worldwide! It would be wonderful to participate in one personally, but for now, I must limit myself to theoretical study, constantly reflecting on everything I learn. Beauty, method and intuition, analysis and synthesis, interpretation, imagination, irregularity, illogic, surprise, counterintuitiveness — these concepts buzz endlessly in my mind.

Regarding the nature of both artistic and scientific activity, my still non-professional understanding insists that both art and science, at their extremes, unfold at the border between the known and the unknown. Artists and scientists strive to break through the barrier, to overcome the transcendental gap between the “familiar, safe” and the “unknown, threatening.” They seek to make the borderline — dangerous in its uncertainty — more comprehensible and safe. Presumably, there is a certain value in overcoming and expanding boundaries, which is why humans are defined as “beings who always strive for more.”

More artworks

And this value of overcoming is realized in the search — whether scientific or artistic. If we ask how exactly this search happens, we inevitably return to the problem of method, which we began this conversation with.

Of course, method exists in art. “In the artistic method,” we read in a concise dictionary of aesthetics, “the main questions of creativity raised by the times are reflected — primarily questions about the nature of artistic generalization, means of expression, and ways of reproducing phenomena of life.”

The fundamental questions — including those about the nature of generalization, means of expression, and ways of reproducing life phenomena — are also contained in the scientific method.

To be fair, contrary to popular belief, method, and indeed the methodology of scientific activity, is a serious problem in science. Scientists continuously question, refine, and modify their methods.

Not merely to achieve a certain result. Results can be obtained almost always, whether as a work of art or as data. However, the goal of research is not merely to accumulate artifacts or data about something.

The main problem of method in science is that the obtained results must meet the fundamental purpose of knowledge: to answer the “eternal” questions about the origin and structure of the universe, the emergence of life and the formation of biodiversity, the place of humans in this world, and finally, the meaning of it all. The method must ensure results that advance us, humanity as a whole, beyond the known, expanding our understanding of the world and ourselves.

If you think about it, art sets exactly the same task for itself. It would be naive to deny that art has a cognitive function.

Most likely, this is the task and function G. Gurdjieff referred to when hinting at the difference between “subjective” and “objective” art.

By “objective,” he possibly meant art capable of expressing objective truths about the world, understandable to a broad audience, rather than only the artist’s “subjective” perceptions of the subject. Like science, ideally, art strives to acquire objective knowledge about the world that can become a common heritage for all.

Of course, method exists in art. “In the artistic method,” we read in a concise dictionary of aesthetics, “the main questions of creativity raised by the times are reflected — primarily questions about the nature of artistic generalization, means of expression, and ways of reproducing phenomena of life.”

The fundamental questions — including those about the nature of generalization, means of expression, and ways of reproducing life phenomena — are also contained in the scientific method.

To be fair, contrary to popular belief, method, and indeed the methodology of scientific activity, is a serious problem in science. Scientists continuously question, refine, and modify their methods.

Not merely to achieve a certain result. Results can be obtained almost always, whether as a work of art or as data. However, the goal of research is not merely to accumulate artifacts or data about something.

The main problem of method in science is that the obtained results must meet the fundamental purpose of knowledge: to answer the “eternal” questions about the origin and structure of the universe, the emergence of life and the formation of biodiversity, the place of humans in this world, and finally, the meaning of it all. The method must ensure results that advance us, humanity as a whole, beyond the known, expanding our understanding of the world and ourselves.

If you think about it, art sets exactly the same task for itself. It would be naive to deny that art has a cognitive function.

Most likely, this is the task and function G. Gurdjieff referred to when hinting at the difference between “subjective” and “objective” art.

By “objective,” he possibly meant art capable of expressing objective truths about the world, understandable to a broad audience, rather than only the artist’s “subjective” perceptions of the subject. Like science, ideally, art strives to acquire objective knowledge about the world that can become a common heritage for all.

More artworks

It turns out that the two types of research activities we are discussing share similar goals. Why not suppose that they could potentially use similar methods? As a researcher, I pose the following question for myself:

Is it possible to develop an artistic method

that, when followed, can expand or deepen

the understanding of the subject under investigation?

If there is ongoing and relevant work in the methodology of scientific research, then why couldn’t work on the method of artistic research also be conducted at an institutional level?

If artists claim to engage in “research” and employ a “method,” it is worth attempting to formulate such a method of artistic research that, like scientific inquiry, leads to the acquisition of objective knowledge.

And at this significant moment, it is crucial to remember that one method alone is not enough for a broader and deeper understanding of the subject. The method organizes the research activity of both scientists and artists and allows obtaining quality data that must then be interpreted. In science, to interpret means to formulate a theory based on the results obtained, which will explain the studied phenomenon.

Interpretation! It is interpretation that transforms accumulated facts into new knowledge.

This unpredictable and inexplicable authorial factor is probably the final frontier of cognitive neuroscience, with the expectation that answering this question will unlock the mystery of what it means to be human.

Interpretation, the unpredictable and inexplicable authorial factor, surprise, and counterintuitiveness — these are all terms used by neuroscientists to describe the process of great scientific discoveries … and the creation of great works of art.

In my understanding, this is the third key point of convergence between art and science.

The first is their shared goal and values — to unravel the mysteries of the universe, from the origin of the world to the meaning of human existence, by overcoming the barrier between the known and the unknown.

The second is the method — which is not yet fully developed in either science or art but roughly meets similar criteria.

And the third is interpretation — the most mysterious and most human aspect of any research activity, which brings all creative people closer to the Creator regardless of the external form their work takes, scientific or artistic.

It follows that art and science are ways to solve the most complex creative problems. Ways so similar that their main difference is probably only the external form, which leads the layperson’s mind to see them as opposite and incompatible. If we set aside external form and superficial details, we will likely find nothing in the very nature of art that contradicts scientific research. Likewise, nothing in the nature of scientific knowledge is incompatible with artistic exploration.

And if we are serious about finding answers to our fundamental questions, why not tear down this “Berlin Wall” and unite our efforts in a joint search for truth? How can this be done?

We are again faced with the problem of method. Fortunately, method is that component in both art and science that we can approach. The goals have long been set.

Interpreting results is a mystery we probably will never fully influence. But we can certainly work on the method.

This is the task I set for myself as a researcher in both “science” and “art”: to develop a method of artistic cognition and to explore the cognitive potential of artistic creativity.

To be continued

Is it possible to develop an artistic method

that, when followed, can expand or deepen

the understanding of the subject under investigation?

If there is ongoing and relevant work in the methodology of scientific research, then why couldn’t work on the method of artistic research also be conducted at an institutional level?

If artists claim to engage in “research” and employ a “method,” it is worth attempting to formulate such a method of artistic research that, like scientific inquiry, leads to the acquisition of objective knowledge.

And at this significant moment, it is crucial to remember that one method alone is not enough for a broader and deeper understanding of the subject. The method organizes the research activity of both scientists and artists and allows obtaining quality data that must then be interpreted. In science, to interpret means to formulate a theory based on the results obtained, which will explain the studied phenomenon.

Interpretation! It is interpretation that transforms accumulated facts into new knowledge.

This unpredictable and inexplicable authorial factor is probably the final frontier of cognitive neuroscience, with the expectation that answering this question will unlock the mystery of what it means to be human.

Interpretation, the unpredictable and inexplicable authorial factor, surprise, and counterintuitiveness — these are all terms used by neuroscientists to describe the process of great scientific discoveries … and the creation of great works of art.

In my understanding, this is the third key point of convergence between art and science.

The first is their shared goal and values — to unravel the mysteries of the universe, from the origin of the world to the meaning of human existence, by overcoming the barrier between the known and the unknown.

The second is the method — which is not yet fully developed in either science or art but roughly meets similar criteria.

And the third is interpretation — the most mysterious and most human aspect of any research activity, which brings all creative people closer to the Creator regardless of the external form their work takes, scientific or artistic.

It follows that art and science are ways to solve the most complex creative problems. Ways so similar that their main difference is probably only the external form, which leads the layperson’s mind to see them as opposite and incompatible. If we set aside external form and superficial details, we will likely find nothing in the very nature of art that contradicts scientific research. Likewise, nothing in the nature of scientific knowledge is incompatible with artistic exploration.

And if we are serious about finding answers to our fundamental questions, why not tear down this “Berlin Wall” and unite our efforts in a joint search for truth? How can this be done?

We are again faced with the problem of method. Fortunately, method is that component in both art and science that we can approach. The goals have long been set.

Interpreting results is a mystery we probably will never fully influence. But we can certainly work on the method.

This is the task I set for myself as a researcher in both “science” and “art”: to develop a method of artistic cognition and to explore the cognitive potential of artistic creativity.

To be continued